No products in the cart.

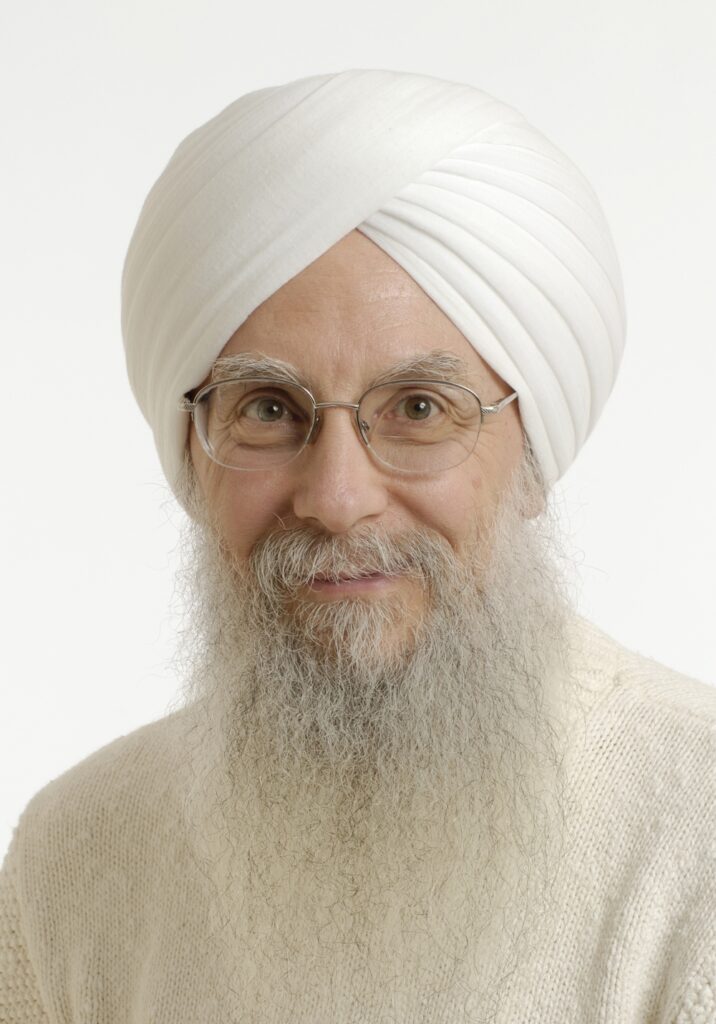

by Nikhil Ramburn and Sat Bir Singh Khalsa, Ph.D

Laughter is a physical reaction seen in humans and some other primates, usually consisting of rhythmic, often audible, contractions of the diaphragm and other parts of the respiratory system. It is a response to an external or internal stimulus and involves different neurological mechanisms than talking, with laughter being under weaker voluntary control than speech. Recently, several physiological and psychological benefits of so-called laughter therapy have been discovered. It appears that laughter reduces the level of stress hormones such as cortisol and epinephrine, while on the other hand, increases endogenous endorphins which activate the body’s opiate receptors for positive euphoric feelings and health-promoting effects.

Laughter also improves immune function as shown by increases in the number of T-lymphocytes and white blood cells in the body. In addition, laughing reduces blood pressure by controlling vasoconstriction and relaxing blood vessels. On the psychological level, laughter therapy helps reduce mood disturbance including unpleasant feelings of tension, anxiety, hatred, and anger while alleviating stress and depression possibly through altering dopamine and serotonin activity. Laughter can also enhance interpersonal relationships and reduce insomnia, memory failure, and dementia.

It seems humor and laughter may prove to be useful as a clinical intervention. As a behavioral strategy, laughter therapy does not require specialized facilities or equipment and is easily accessible to patients who may have severe restrictions due to illness. In an attempt to better understand the role of humor in improving wellbeing amongst patients suffering from life-limiting illness, researchers at the University of Bonn in Germany conducted a systematic review of 13 humor interventions or assessments in palliative care. Despite limitations in both quantity and quality of studies, the evidence suggests that humor is indeed an appropriate and useful resource in palliative care with one of the key benefits being an increased pain tolerance, which results in a reduced need for pain medication and its negative consequences and side effects.

Laughter yoga is a modification of laughter therapy. The key pioneer of laugher yoga, Dr. Madan Kataria, recognized the potential behavioral and clinical benefits of laughter and started a laughter club in Mumbai, India during his time there as a medical student. Dr. Kataria was aware of the potential of yoga to facilitate laughter, including the similarities between yogic breathing (pranayama) exercises and laughter. He is largely responsible for spreading laughter yoga (LY) across the globe into general public and health care settings.

A recent systematic review of the literature, evaluating studies published from 1995 to 2017, aimed to assess the mental health outcomes of LY. The researchers analyzed six experimental studies, all delivered in a group format with warm-up exercises, deep breathing exercises, a childlike playfulness, and laughter exercises. This systematic approach mirrors LY. The findings revealed that the most promising effect of laughter yoga was the improvement in depressive symptoms. Unfortunately, the relatively lower quality of research in this new field is at present insufficient to allow for the evidence to justify drawing strong conclusions in support of LY’s impact on mental health when compared to other group interventions.

Nonetheless, several newer studies have shown encouraging psychophysiological changes after LY practice. In a randomized controlled trial (RCT) study, one hundred and twenty (120) healthy university students were allocated to either LY, watching a comedy movie (which elicited spontaneous laughter), or reading a book. The LY program lasted thirty (30) minutes and was conducted in a group setting where a laughter leader assisted the subjects in simulated laughter and yogic breathing. Researchers found that cortisol levels (a stress hormone) and the cortisol / dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) ratios (a counterbalancing hormone to cortisol) significantly decreased in both the LY and comedy movie groups suggesting decreased stress levels and positive psychophysiological benefits. However, the effect of spontaneous laughter (movie group) on the cortisol dynamics lasted longer than that of LY suggesting greater psychophysiological benefits from spontaneous laughter than the laughter in LY.

In another recent study of longer duration, participants took part in a 45-minute LY session once per month for six months. Repeated sessions appeared to have many psychological benefits as measured by a Profile of Mood States questionnaire. The participants reported less anxiety and more vigor, and their blood samples (drawn at each session) showed decreased adrenocorticotropic hormone and cortisol values, which related to the participants’ significant decrease in stress after the fourth LY session.

Another study of thirty-eight (38) male nursing students from the Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery at the Isfahan University of Medical Sciences in Iran found that LY was associated with improvement in sleep disorders, reduced anxiety and depression, and increased social function. Apart from the psychological benefits noted previously, studies also indicated that LY has physical benefits, such as the increased demand on trunk muscles which play a key role in stabilizing the spine.

One study compared the activation of trunk muscles in LY with crunch and back lifting exercises. Researchers measured surface electromyography of five trunk muscles and found that LY resulted in greater activation of the internal oblique muscle, and the external oblique activation was comparable with crunch and back lifting exercises. Overall, laughter seems to be a good activator of trunk muscles but further research is required to determine whether LY exercises can improve neuromuscular recruitment and improve spine stability, a faculty which can deteriorate with age.

In elderly populations, LY practice may provide several benefits in addition to trunk muscle engagement. Older adults in residential care commonly face elevated risks of depression. Researchers from the Allameh Tabatabai University in Tehran, Iran set out to determine how LY and exercise therapy could impact depression scores. Seventy (70) depressed elderly women were randomized into LY, exercise or a control group. The LY group received a brief talk about something delightful like national and religious ceremonies and having positive attitudes to everyday life affairs before participating in the LY exercises. The results of the study revealed a significant decrease in depression scores of both the LY and exercise groups in comparison to the control group. In addition, the LY group showed a significant increase in life satisfaction compared to the control group, whereas the exercise group showed no such improvement.

Despite the encouraging findings, this study has come under criticism for eliciting positive emotions at the outset of the program, even before the laughter exercises began. A more recent study from the La Trobe University in Melbourne found physiological benefits in twenty-eight (28) elderly residents in residential care homes. In that study, LY was associated with lower blood pressure and improved mood, both of which can have positive downstream effects on cardiovascular health.

Finally, LY may prove to be a useful complementary therapy for cancer patients. Since cancer is usually accompanied by considerable stress, it is conceivable that LY could relieve the cancer patients’ stress before chemotherapy. Indeed, researchers found that LY was able to decrease stress in thirty-seven (37) cancer patients at the Shohada Tajrish Hospital in Iran before their chemotherapy. Since stress meaningfully increases cancerous cell activity and causes the involved cells to resist chemotherapy, LY may prove an important complement in the treatment of cancer.

In summary, the current body of research evidence suggests that LY is effective and scientifically supported as a stand-alone or complementary therapy. Although, further research is needed to fully understand the mechanisms underpinning the somewhat forced laughter in LY and its physiological differences to spontaneous laughter. Future research should avoid combining positive-emotion-inducing factors such as prompts about a positive attitude with LY and measure mood at baseline and post intervention in larger population sizes.

An upcoming RCT by the Hong Kong Polytechnic University aims to determine the feasibility of using an LY intervention on patients with major depressive disorder, in which seventy-two (72) community dwelling people with co-morbid symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress will be recruited into the study and randomized into either the LY group or a treatment-as-usual group. Undoubtedly, such research studies will continue and hopefully add to the positive findings to date.

Nikhil Rayburn grew up practicing yoga under mango trees in the tropics. He is a certified Kundalini Yoga teacher and has taught yoga to children and adults in Vermont, New Mexico, Connecticut, India, France, and Mauritius. He is a regular contributor to the Kundalini Research Institute newsletter and explores current yoga research.

Sat Bir Singh Khalsa, Ph.D. is the KRI Director of Research, Research Director for the Kripalu Center for Yoga & Health, and Assistant Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School. He has practiced a Kundalini Yoga lifestyle since 1973 and is a KRI certified Kundalini Yoga instructor. He has conducted research on yoga for insomnia, stress, anxiety disorders, and yoga in public schools. He is editor in chief of the International Journal of Yoga Therapy and The Principles and Practice of Yoga in Health Care and author of the Harvard Medical School ebook Your Brain on Yoga.

KRI is a non-profit organization that holds the teachings of Yogi Bhajan and provides accessible and relevant resources to teachers and students of Kundalini Yoga.

More Related Blogs