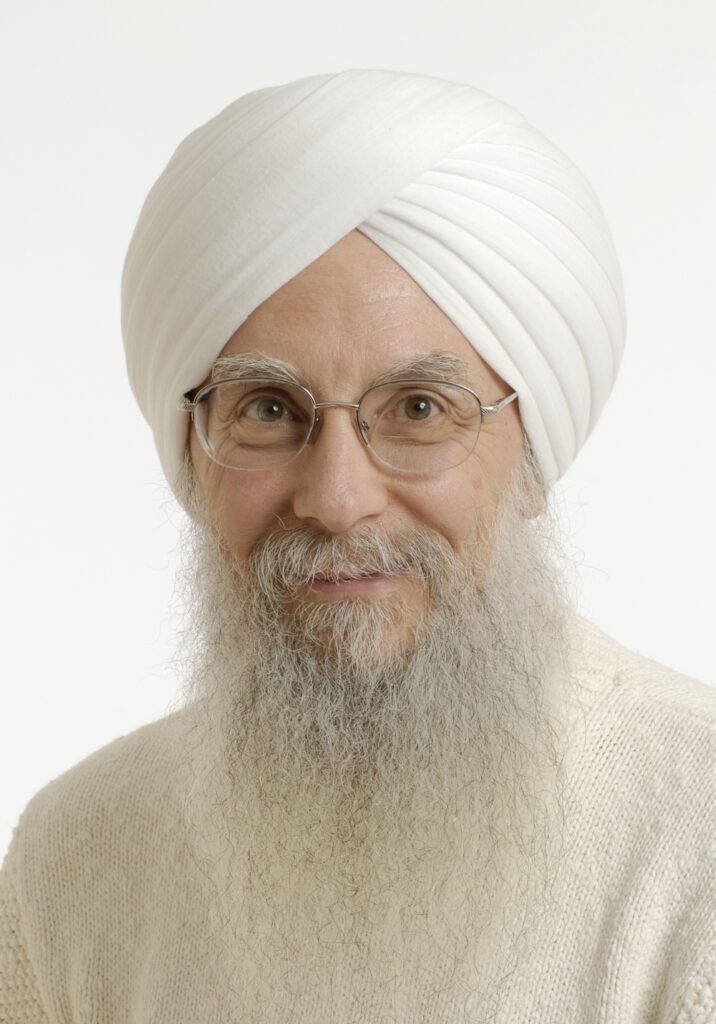

by Sat Bir Singh Khalsa, Ph.D.

Unlike animals, the respiratory system is under voluntary control in humans, which has allowed for the development of voluntary breath regulation practices in yoga and other behavioral disciplines such as Tai Chi and Qi Gong. The aim of these breathing practices is to change psychological and physiological state in a beneficial way. Research on slow yogic breathing has demonstrated numerous psychophysiological effects including reduction of autonomic arousal, increase in heart rate variability, improved oxygen and carbon dioxide exchange, and changes in the respiratory system’s sensitivity to these gases.

Unlike animals, the respiratory system is under voluntary control in humans, which has allowed for the development of voluntary breath regulation practices in yoga and other behavioral disciplines such as Tai Chi and Qi Gong. The aim of these breathing practices is to change psychological and physiological state in a beneficial way. Research on slow yogic breathing has demonstrated numerous psychophysiological effects including reduction of autonomic arousal, increase in heart rate variability, improved oxygen and carbon dioxide exchange, and changes in the respiratory system’s sensitivity to these gases.

An interesting feature of yoga and slow breathing practice over the long term is the capability of reducing spontaneous breathing frequency, that is the respiratory rate when one is alert and relaxed and not actively trying to control the breath in any way. In the general population, the spontaneous respiratory rate is commonly between 10 and 20 breaths per minute and often involves little movement of the abdomen and is predominantly a shallow, more rapid chest breathing pattern. Slow yogic breathing emphasizes movement of the abdomen, or so-called abdominal or belly breathing, which allows for deeper breaths. It is likely that slower abdominal breathing is the more natural and healthful breathing frequency than the higher 10-20 breath per minute rate and, in fact, this slow breathing comes naturally to infants and children. Over time, as we age, people tend to adopt the chest breathing pattern. Contributing factors to this change may be higher levels of stress and/or anxiety, which tend to alter breathing to faster rates, and cosmetic/psychosocial factors such as avoiding the undesirable physical appearance of having the abdomen extended. In yoga and pranayama practice it is believed that the respiratory pattern can be modified over time to the more beneficial, slower, abdominal breathing pattern and some research has supported this contention.

In a Belgian study published in 1981 in the Journal of Applied Physiology, the spontaneous breathing patterns of 8 accomplished hatha yoga practitioners showed markedly different respiratory characteristics as compared with control subjects matched for sex, height, and age. The spontaneous breath rate in the yoga practitioners was 5.5 breaths per minute on average, significantly lower compared with the 13.4 breaths per minute in non-practitioners. Accordingly, the tidal volume (the lung volume of air displaced between normal inhalation and exhalation when breathing normally), in the yoga practitioners was 1.03 liters, significantly larger than the 0.56 liters in the non-practitioners. The authors suggested that the slower breathing rate was directly attributable to effects of the yoga and pranayama practices over time, proposing hypothetically that these changes could be mediated either by changes in stretch receptor characteristics in the chest or by a chronic reduction in sympathetic drive. However, a weakness of such a retrospective study of individuals who self-selected into yoga practice is that it is not possible to exclude the possibility that people with altered breathing patterns are naturally attracted to yoga practice. To address this concern definitively, prospective randomized controlled trials with naïve subjects are required and a number of studies have done exactly this, thereby addressing this concern.

In a research study by a French team of investigators published in 2005, 16 subjects who had not practiced yoga previously underwent an intervention of yogic ujjayi breathing involving very slow, deep breaths at 2 to 3 breaths per minute with a sustained breath-retention after each inspiration and expiration. They did this for 20 to 30 minutes daily for 2 months. The researchers reported that the spontaneous respiratory frequency was significantly reduced from 19.6 breaths per minute to 13.6 breaths per minute, and also that the increase in the duration of the exhale contributed most to this slower breathing pattern. One of the most recent studies to confirm this capability was conducted in India with 60 subjects naïve to yoga practice aged 20-50 years. They practiced slow breathing at a rate of about 6 breaths per minute for 8-10 minutes twice daily for 3 months. Their respiratory rate before the intervention was 20 breaths per minute and was reduced significantly to 17 breaths per minute afterwards. The study also reported a statistically significant reduction in spontaneous resting heart rate as well as a significant shift from a predominantly chest-thoracic breathing pattern to a breathing pattern with more abdominal-belly movement. Although such studies are supportive of the ability of humans to self-regulate their breath frequency to become lower, scientists often need additional information that elucidates the mechanisms involved before they can be definitively convinced. This is difficult in human subjects given the challenge of recording neural activity within the central nervous system. It would be ideal if there was an animal model of this phenomenon that would lend itself more easily to such mechanistic study. Fortunately, we now have a rat model of slow breathing.

A research team from Emory University published a paper in 2017 in the journal Frontiers in Physiology entitled “Slow Breathing Can Be Operantly Conditioned in the Rat and May Reduce Sensitivity to Experimental Stressors”. In this study they were successfully able to condition rats to breath slowly over multiple training sessions over 2 weeks by using a flashing light stimulus, which rats do not like. In the conditioning training with exposure to the flashing light, rats were able to turn off the light when they reduced their respiratory rate below a threshold respiratory rate of 80 breaths per minute (rats breath much more rapidly than humans). The conditioned rats reduced their average respiratory rate significantly from an average of 92 breaths per minute to 81 breaths per minute. This result shows unequivocally that it is possible for mammals to change their spontaneous respiratory rate with training. However, the study took an important step further by then challenging both the normal and slow-breathing rats with stressful stimuli. An animal model of this phenomenon would lend itself more easily to mechanistic study and, fortunately, we now have a rat model of slow breathing.

Studies have shown that slow breathing has numerous psychophysiological benefits and that breath regulation is one of the most commonly used practices immediately following initiation of yoga practice by beginners. There is, therefore, a significant potential for promoting the value of breath regulation practices in society, particularly slow breathing, which is relatively easy to learn and implement in day-to-day, real-life circumstances. The demonstration that humans can slow their spontaneous respiratory rate with practice, and the virtue of having an animal model of this that will lead to future research on the mechanism of these changes, suggests that we are moving quickly towards certainty and confidence regarding the practical benefits and application of slow yogic breathing.

Sat Bir Singh Khalsa, Ph.D. is the KRI Director of Research, Research Director for the Kripalu Center for Yoga & Health, and Assistant Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School. He has practiced a Kundalini Yoga lifestyle since 1973 and is a KRI certified Kundalini Yoga instructor.

He has conducted research on yoga for insomnia, stress, anxiety disorders, and yoga in public schools. He is editor in chief of the International Journal of Yoga Therapy and The Principles and Practice of Yoga in Health Care and author of the Harvard Medical School ebook Your Brain on Yoga.

KRI is a non-profit organization that holds the teachings of Yogi Bhajan and provides accessible and relevant resources to teachers and students of Kundalini Yoga.

More Related Blogs