by Sat Bir Singh Khalsa, Ph.D.

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) is a psychiatric condition that was previously classified as one of the anxiety disorders, specifically as a personality disorder, but is now classified in the new diagnostic category of Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders. Patients with OCD experience uncontrollable and continuously reoccurring thoughts or obsessions and/or compulsive behaviors that are severe enough to interfere with their lives. Obsessions include symptoms such as uncontrollable fear of germs or contamination, aggressive thoughts, unwanted forbidden or taboo thoughts on sex, religion, or harm, and insistence on things being symmetrical or in order. Compulsions are uncontrollable, ritualistic, or habitual behaviors in response to obsessive thoughts such as excessive cleaning or handwashing, ordering objects in a very precise way, counting, and repeatedly checking to see if everyday tasks have been done. Symptoms of OCD have been portrayed by actor Jack Nicholson in the movie As Good as It Gets and actor Tony Shalhoub in the TV series Monk. Although these showed some humorous circumstances, OCD is a bona fide mental health disorder that can cause significant suffering. The USA Network that aired Monk, launched a public service campaign to increase awareness of OCD and its treatment and the show’s website provides OCD information.

The overall prevalence of OCD in the population is about 1 percent, with about half of patients exhibiting a serious impairment; it is higher in females and is highest in young adulthood but decreases with age. Potential risk factors for OCD include a genetic predisposition, specific abnormalities in brain structure and function, and childhood trauma although the underlying cause of this disease is unknown. Conventional treatments have included pharmaceuticals, psychotherapy including cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and brain stimulation therapies. However, despite significant improvements with these treatments many patients are still left with significant symptoms, suggesting the need for additional treatment strategies.

Research on mind-body therapies, such as progressive relaxation, have shown some benefit. One of the first reports of meditation/mindfulness for OCD was a single-patient case report published in 2008 involving mindfulness researcher James Carmody showing that an adapted form of the Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) program yielded significant improvement in the score of the clinician-administered Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (YBOCS), the most common clinical instrument for this disorder. At a 3-month follow-up, the patient exhibited only mild OCD symptoms with improved quality of life and functioning including return to full time work. However, he noted “a need for continued mindfulness practice in order to refine his ability to bring ‘mindfulness to everyday OCD.’”. Subsequently, a number of OCD studies including randomized trials (RCTs) have demonstrated the efficacy of mindfulness-based treatments such as the Mindfulness Based Cognitive Therapy program (an MBSR derivative) and so-called “third-wave” therapies, melding mindfulness-related practices with CBT. A 2019 review of “new-wave” OCD treatment studies in the Indian Journal of Psychiatry by authors from the prestigious National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences (NIMHANS) in India, identified 40 published trials that provide encouraging evidence for these therapies on OCD symptoms.

The basic premise behind the use of meditation/mindfulness-based approaches is the increase, with practice, in the self-regulation of attention, which is at the heart of meditation and yogic practices as originally described in Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras. This ultimately leads to the capability of meta-cognition, the skill of self-regulation of thought processes and the realization that one’s true identity/self is beyond thought processes, and therefore that thought processes can be regulated, even if those thinking patterns are dysfunctional, as they are in OCD. An example of this can be seen in a quote from a subject in a 2012 qualitative study of MBCT in Germany: “When this urge comes, like let’s say, I want to step out right now and wash my hands, that I then first pause for a second and remind myself to also be mindful with myself…”. Recent research on mindfulness-based approaches is now actually investigating which specific aspects of mindfulness are most effective in countering obsessive intrusive thoughts (OITs). A 2018 paper in the journal Mindfulness concluded that “…acting with awareness and acceptance may confer protective characteristics in relation to OITs, but that the observe facet may reflect a hypervigilance to OITs. Mindfulness-based prevention and intervention for OCD should be tailored to take account of the potential differential effects of increasing specific facets of mindfulness.”

Research on yoga practices for OCD actually predate studies of meditation/mindfulness alone. In 1996, a case series yoga-for-OCD-treatment study was published in the International Journal of Neuroscience by David Shannahoff-Khalsa. The intervention consisted of a series of physical exercises followed by multiple specific meditations that incorporated posture, breath regulation, and mental focus (some of which could be practiced for up to 31 minutes) intended to reduce anxiety, stress, and mental tension from Kundalini Yoga as taught by Yogi Bhajan. It also included a key yoga practice thought to be specific for OCD, a specific left-nostril breathing meditation that included breath retention after the inhale and exhale. Most of the subjects completing the trial showed a substantial average improvement of 54 percent in YBOCS scores at three months, with some of these experiencing continued improvement up to one year. This study was followed by an RCT published in 1999 that added researchers from the Scripps Research Institute and the University of California, San Diego. The primary treatment group practiced an hour-long version of the Kundalini Yoga practice from the earlier study, whereas the other group practiced relaxation response and mindfulness meditation practices for 30 minutes. After 3 months of treatment, improvements in the yoga group were significantly greater than those in the meditation group on the YBOCS and on another measure of obsessive compulsiveness and mood disturbance. Subjects in the meditation control group then underwent the yoga protocol, and the now-combined treatment group showed continuing additional improvements in YBOCS scores continuously through the 15-month evaluation. The degree of improvement at 3 months was clinically significant and on a par with conventional pharmaceutical treatment suggesting that this yogic therapy is a viable, and potentially preferable, behavioral intervention.

The latest RCT study of Kundalini Yoga for OCD in Brazil has been published in the prestigious journal Frontiers in Psychiatry in November of 2019. For this study, Shannahoff-Khalsa was joined by a team that included researchers from the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Sao Paulo, and together completed a larger RCT with a similar design to the study in the 1999 paper, with the control group practicing the relaxation response meditation. After four-and-a-half months of treatment, the improvement in the YBOCS score was significantly better than that in the control condition. Subjects completing the yoga treatment experienced a 40 percent improvement, which was similar to that for the previous study; about one third of the patients in the yoga group were in full remission from the disease. In addition, secondary measures from validated questionnaires for mood disturbance, anxiety, and depression also showed improvements with yoga that were significantly better than the control group. In a second phase of the study, in which control subjects then also underwent the yoga treatment protocol, the results for the YBOCS and secondary measures were again similar to the previously published RCT in which improvements continued through about one year of treatment time. The authors concluded that Kundalini Yoga as taught by Yogi Bhajan “shows promise as an add-on option for OCD patients unresponsive to first line therapies”.

The only other trial evaluating a yoga intervention for OCD was published in 2016 by a NIMHANS research team. This trial was largely designed as a preliminary test and refinement of a hatha yoga protocol but did include a small single group treatment trial. This study reported a statistically significant improvement in the average YBOCS score for 10 subjects completing two weeks of the treatment with score improvements similar to those for the Kundalini Yoga trials.

Clearly, there is now reasonable preliminary evidence for yoga as a treatment modality for OCD. The meditative component of yoga may be one mechanism by which yoga is exerting clinical improvements, and it remains to be determined how much the postures and breath regulation practices may also be contributing.

Additional research is warranted for yoga as a behavioral treatment that provides an additional option for patients, which is free from side effects of pharmaceuticals and may provide benefits in patients who have had experienced insufficient improvement with conventional treatments.

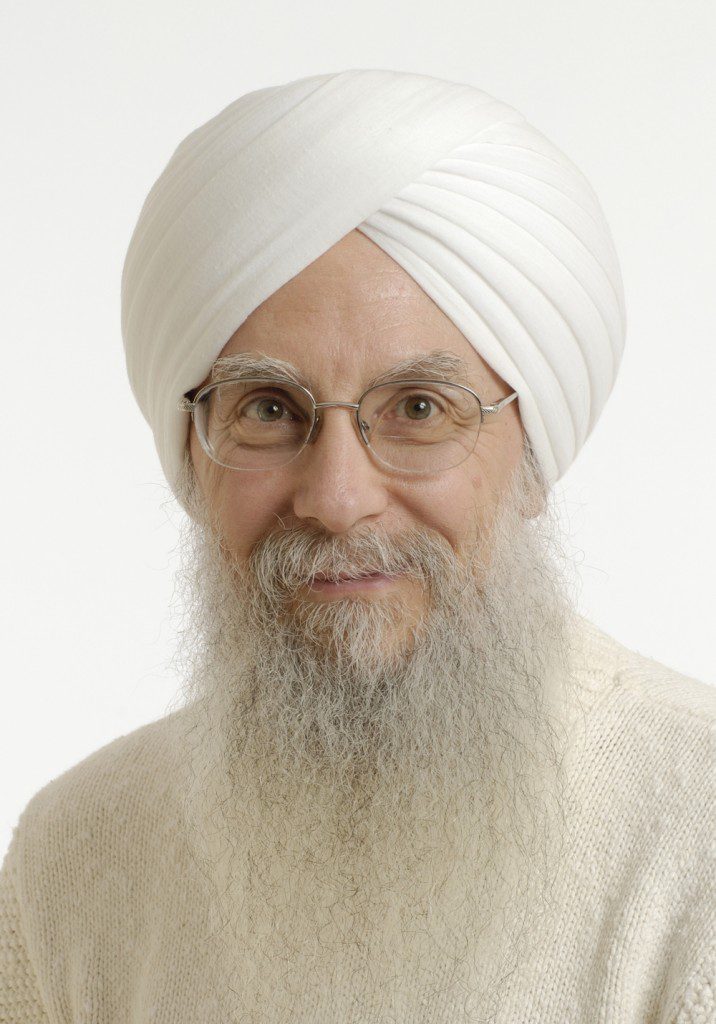

About The Author

Sat Bir Singh Khalsa, PhD

The major focus of my research interest lies in the field of Mind-Body Medicine. Specifically, I am interested in the evaluation of the clinical effectiveness and basic psychophysiological mechanisms underlying the practice of yoga and meditation techniques. These behavioral techniques include specific manipulations of respiratory frequency and tidal volume, maintenance of body postures and stretching exercises, and meditation and mindfulness, which involves relaxed control of attention. These practices are known to produce a coordinated psychophysiological response that has been called the relaxation response, which is associated with a reduction in psychophysiological arousal and a sense of relaxation and well-being. These techniques have been found to be effective for many disorders that have a psychosomatic component and are exacerbated by stress. As behavioral techniques, these practices provide patients with the opportunity for direct involvement in their healthcare, not only reducing the severity of their disorder, but also improving their quality of life. In many cases, these techniques are more effective than existing pharmacological treatments, many of which have side effects.

I have practiced a yoga lifestyle since 1972 and I am a certified instructor in Kundalini Yoga as taught by Yogi Bhajan. I am the Director of Yoga Research for the Yoga Alliance and the Kundalini Research Institute, Research Associate at the Benson Henry Institute for Mind Body Medicine, Research Affiliate of the Osher Center for Integrative Medicine. I have conducted clinical research trials evaluating yoga interventions for insomnia, post-traumatic stress disorder, chronic stress, and anxiety disorders and in both public school and occupational settings. I work with the International Association of Yoga Therapists to promote research on yoga and yoga therapy as the chair of the scientific program committee for the annual Symposium on Yoga Research and as editor-in-chief of the International Journal of Yoga Therapy. I am medical editor of the Harvard Medical School Special Report An Introduction to Yoga and chief editor of the medical textbook The Principles and Practice of Yoga in Health Care.

KRI is a non-profit organization that holds the teachings of Yogi Bhajan and provides accessible and relevant resources to teachers and students of Kundalini Yoga.

More Related Blogs