By Nikhil Ramburn and Sat Bir Singh Khalsa, Ph.D.

The most common breathing practice in yoga is long, slow, deep breathing. However, despite its simplicity and multiple benefits, it is also relatively misunderstood. The slow breathing practices in yoga are not simply slower, they are also deeper, with the diaphragm and lungs expanding more fully with each breath. Yogic breathing involves the noticeable movement of the abdomen, which extends outwards on each inhale, thereby earning it the name of abdominal or belly breathing. Apart from simple, slow, deep breathing, yogic breathing or pranayama, practices also include modified techniques such as Ujjayi, which involves a slight constriction of the glottis to create an audible breath. Other yogic breathing patterns may call for different breathing frequencies, different breath inhalation, retention, and exhalation ratios, segmented inhales and exhales, and breathing through specific nostrils. The deeper expansion of the lungs in simple, long, slow, yogic breathing effectively increases the lung surface available for gas exchange and so it is more efficient use of the lungs. In addition, dead space ventilation (movement of air during breathing in the trachea between the mouth and lungs that does not participate in gas exchange) is relatively reduced. The resulting increase in efficiency is equivalent to one possessing a larger lung.

Unfortunately, the understanding of the accurate benefits of yogic breathing is often compromised by certain claims and misconceptions. The most common of these is the notion that slow, yogic breathing increases oxygen in the blood and that most of the public, who are not privy to practicing this type of breathing, are walking around chronically oxygen deprived. In fact, unless one has a respiratory condition, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or one is at high altitude, blood oxygen levels are normally well maintained at very high levels. It should be noted that respiratory physiology is a complicated issue whose details are outside of the scope of this article. However, the reality is that both slow and rapid yogic breathing practices, if done appropriately, do not yield significant changes in oxygen or carbon dioxide levels. The main reason for this is that the effect of the deeper breath in long slow deep breathing is counterbalanced by the slower respiration rate. Deeper breathing with a typical respiration rate would actually lead to clinical hyperventilation, a potentially harmful state, which should be taken into account when practicing yogic breathing.

Research on the long slow pranayama practice, when practiced appropriately, has been shown to slightly improve gas exchange under normal conditions. In early studies in 1964 at the Department of Psychiatry at Yale University, research fellow K.T. Behanan (trained in yoga at the Kaivalyadhama Yoga Institute in India) examined the effects of a series of pranayama practices on himself, with the results published in both a monograph and the Journal of Applied Physiology by his mentor. Three representative patterns of yogic breathing were tested, namely Ujjayi, Kapalabhati, and Bhastrika. While these techniques required a 12-35 percent increase in oxygen consumption above baseline, the relaxed breathing that immediately followed showed little indication that the subject had been exerting himself. A thorough study by Frostell et al. in 1983 using state of the art respiratory physiological research measures in advanced pranayama practitioners, made it clear that both slow and fast types of pranayama yielded minimal changes in both oxygen and carbon dioxide levels. A more recent pranayama research study published in the journal Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine in 2013, had 17 yoga-naive participants tested to see if Ujjayi resulted in greater oxygen saturation when compared to regular slow yogic breathing. The results showed the greatest improvements in slow breathing without Ujjayi, likely due to the increased respiratory effort. However, Ujjayi did result in greater oxygen saturation. The researchers concluded that simple slow breathing with equal inspiration/expiration is the best technique for yoga naive subjects.

In addition to these studies performed under normal conditions, there is a growing body of evidence that yogic breathing improves gas exchange under altered, challenging conditions as well. In 1968, Shanker Rao from the Armed Forces Medical College in Pune, India looked at one subject who attempted yogic respiratory control at two different altitudes. The observations were carried out in the southwestern foothills of the Himalayas (12,500 ft.) and in Pune (1,800 ft.). He observed that the subject met increased demands for oxygen at high altitude by using long slow yogic breathing, which was effectively improving respiratory efficiency by increasing tidal volume (the total volume of air exchanged in each breath) instead of increasing the frequency of respiration.

Recent studies with a larger group of subjects support these early findings. In 2001, Luciano Bernardi et al. conducted a study in Albuquerque NM, comprising of 19 controls and 10 western yoga trainees to test breathing patterns and autonomic modulation at simulated high altitude. The researchers found that yoga trainees maintained better blood oxygenation without increasing ventilation (slow yogic breathing being a more efficient breathing method) and had reduced sympathetic activation when compared to controls. A subsequent study by Bernardi et al. looked at Caucasian yoga trainees, Nepalese Sherpas and Himalayan Buddhist monks. They found that yoga trainees were able to maintain oxygen exchange rates at high altitude that resembles the Himalayan natives. Therefore, respiratory adaptations induced by yoga practice may represent an efficient strategy to cope with altitude-induced hypoxia (inadequate oxygen supply). Another recent study lead by Colonel Himashree of the Indian Army and published in 2016, further confirmed these findings with a large sample size of two hundred Indian soldiers divided equally between an exercise control and yoga practice group. Indeed, the yoga group performed better at high altitude in a number of health indices such as respiratory rate, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, and anxiety rates.

In summary, slow yogic breathing is the most efficient way to ventilate and exchange oxygen and carbon dioxide. However, in addition to this benefit, long slow yogic breathing is also known to also offer numerous additional benefits including beneficial effects on heart rate variability, the chemoreflex response, autonomic function, and even on mood and mental health.

Nikhil Rayburn grew up practicing yoga under mango trees in the tropics. He is a certified Kundalini Yoga teacher and has taught yoga to children and adults in Vermont, New Mexico, Connecticut, India, France, and Mauritius. He is a regular contributor to the Kundalini Research Institute newsletter and explores current yoga research.

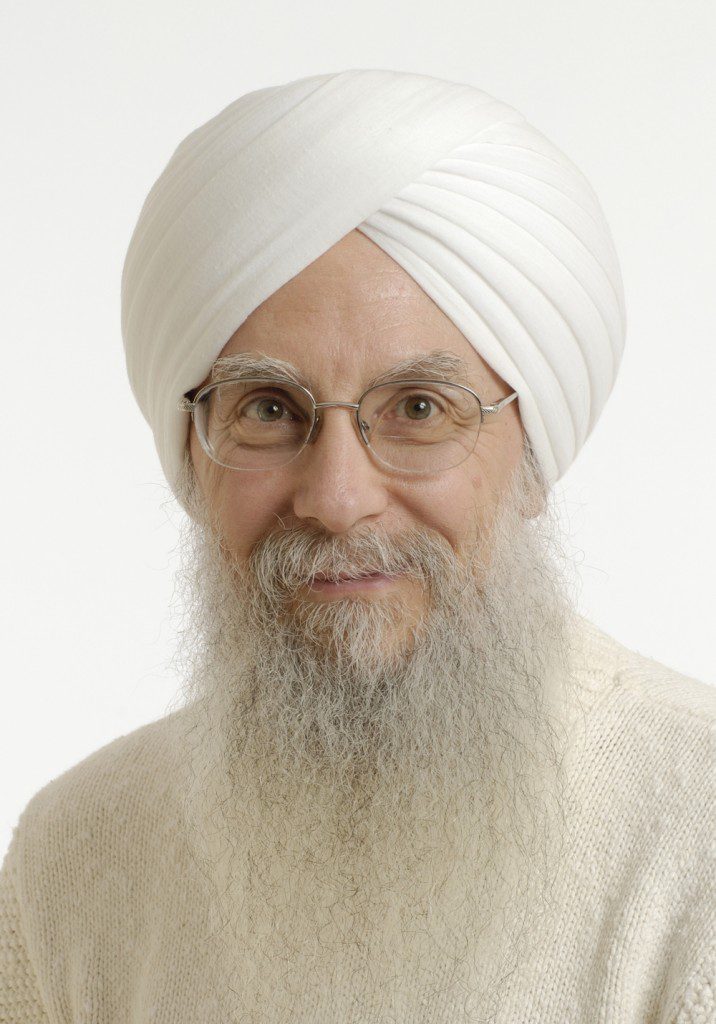

Sat Bir Singh Khalsa, Ph.D. is the KRI Director of Research, Research Director for the Kripalu Center for Yoga & Health, and Assistant Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School. He has practiced a Kundalini Yoga lifestyle since 1973 and is a KRI certified Kundalini Yoga instructor. He has conducted research on yoga for insomnia, stress, anxiety disorders, and yoga in public schools. He is editor in chief of the International Journal of Yoga Therapy and The Principles and Practice of Yoga in Health Care and author of the Harvard Medical School ebook Your Brain on Yoga.

KRI is a non-profit organization that holds the teachings of Yogi Bhajan and provides accessible and relevant resources to teachers and students of Kundalini Yoga.

More Related Blogs