by Sat Bir Singh Khalsa, Ph.D.

Historically, yoga has been fundamentally a spiritual practice to attain unitive states of consciousness or the samadhi state. However, given the fact that yoga employs both physical (asana, pranayama, relaxation) and cognitive (meditation) practices to foster self-regulation and optimize human functioning, its relevance to restoring optimal functioning in disease states has been an obvious possibility. Even in the 15th century Hatha Yoga Pradipika are statements attesting to the benefits of specific yogic practices in reducing obesity, removing abdominal disorders, fatigue, and edema and generally “destroying all diseases” including leprosy.

By the beginning of the 20th century, we see the systematic application of yoga as a treatment for therapeutic conditions in India. The Yoga Institute in Mumbai documented the application of yoga as therapy to 124 patients in 1918-19, reporting “Symptom relief in most cases. Occasional verification by physician.” In a two-year period from 1920-22, 2,000 patients were treated with the identical claim of clinical improvement. Similarly, the Kaivalyadhama Yoga Institute, founded in 1924 and also in Mumbai, was reporting in its 1930 volume of its research journal Yoga Mimamsa that “nearly two thousand people have been treated…as…patients. People suffering from constipation, dyspepsia, auto-intoxication, nervous debility, asthma, piles, seminal weakness, heart troubles and a variety of other diseases have found great relief from Yogic Therapy.” Unfortunately, such vague descriptions of clinical benefit clearly failed to meet any kind of acceptable scientific or clinical criteria that provide confidence in attesting to the safety and efficacy of yoga therapy.

Even as late as 1964 in a four-paragraph report by Higashi in the prestigious medical journal Lancet we are still provided with minimal documentation of specific quantitative details of clinical improvement. In a Tokyo sanatorium, they applied a daily 10-minute pranayama practice over a year to 50 male schizophrenic patients. The clinical outcome is marginally and vaguely described with the text: “About the beginning of the third month, we noticed that the patients gathered spontaneously at the usual place. When the session ended a quiet atmosphere prevailed for some time. Moreover the average number of patients participating was 81% as against 56% in the previous year.” It’s conclusion stated, “An exercise which controls breathing favourably influences the psychiatric regimen.”

Given the proliferation of yoga therapy in India, yet conducted without adequate research and clinical documentation, the Ministry of Health of the Government of India created a committee in 1960 led by well-known leading yoga researcher Dr. B.K. Anand to evaluate yoga therapy claims. It collected information from 71 institutions across India, visiting 19 select institutions, and yielded the 1962 Ministry of Education 72-page document entitled “Report of the Committee on Evaluation of Therapeutical Claims of Yogic Practices.” It concluded that for lack of proper data and the personnel adequately trained to collect such data, it was not possible for it to evaluate Yogic therapy claims. It further stated, “Unless a scientific assessment of the patient treated by Yogic therapy is organized under controlled conditions, it will not be possible to evaluate the important therapeutic claims of Yoga.”

Finally, in 1966 we see the publication of perhaps the first acceptably-reported biomedical research evaluation of yoga therapy by Vahia, Vinekar and Doongaji in an 8-page paper in the British Journal of Psychiatry. In this case series study conducted with the Kaivalyadhama Institute they describe results of 4 to 6-week yoga therapy sessions with patients at the K.E.M. Hospital in Mumbai. A table in the report describes multiple characteristics including demographics, diagnoses, treatment durations, and quantitative percent improvements for 30 patients with psychosomatic conditions such as anxiety, depression, headache, insomnia, cognitive difficulties and other stress-related symptoms. They further included 3 detailed case reports that were presented in the format and with the amount of detail that would be viewed as reasonable from a modern clinical research presentation perspective.

It was not long after this that we see the first humble clinical trial publication in yoga therapy published in Yoga Mimamsa in 1967, to be followed by the first randomized controlled trials on yoga for hypertension by yoga researcher Chandra Patel in the U.K. in the early 70’s. From that first 1967 trial of yoga for asthma through to 2003, there were approximately 150 clinical trials published, a number which tripled to about 450 publications 10 years later by 2013. We are now fortunately in the position in this field in that we are experiencing an exponentially increasing growth in the number of clinical yoga research studies and publications with more and more of the rigorous randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses necessary to justify recommendation of continued yoga therapy research and implementation of yoga interventions in modern medicine.

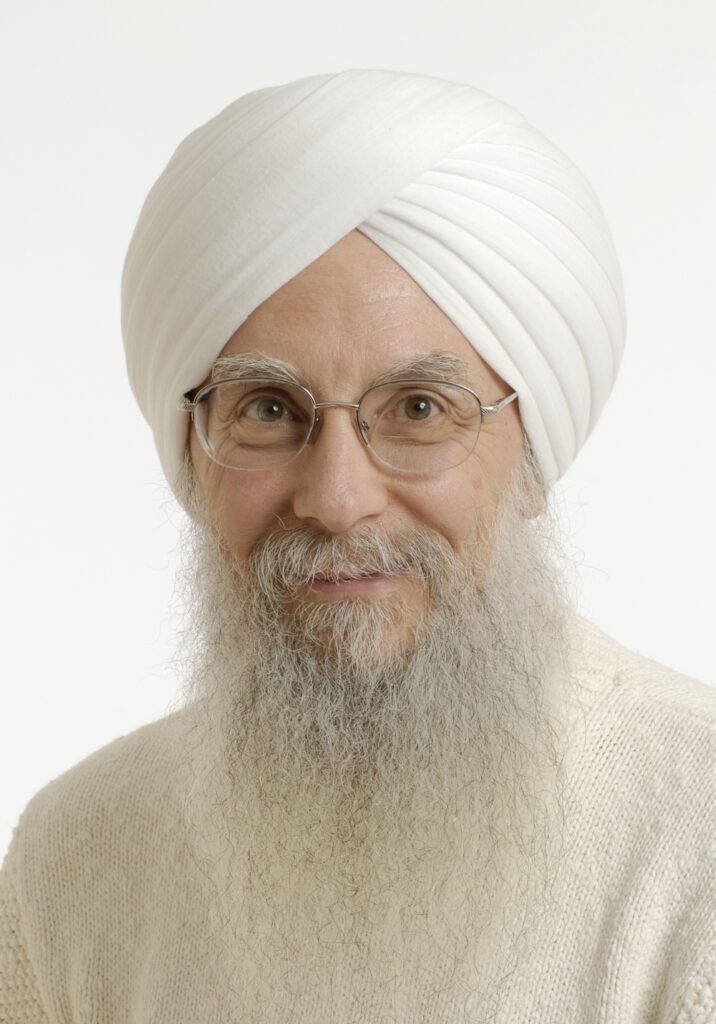

Sat Bir Singh Khalsa, Ph.D. is the KRI Director of Research, Research Director for the Kripalu Center for Yoga & Health, and Assistant Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School. He has practiced a Kundalini Yoga lifestyle since 1973 and is a KRI certified Kundalini Yoga instructor.

He has conducted research on yoga for insomnia, stress, anxiety disorders, and yoga in public schools. He is editor in chief of the International Journal of Yoga Therapy and The Principles and Practice of Yoga in Health Care and author of the Harvard Medical School ebook Your Brain on Yoga.

Teacher

KRI is a non-profit organization that holds the teachings of Yogi Bhajan and provides accessible and relevant resources to teachers and students of Kundalini Yoga.

Français

Français Deutsch

Deutsch Italiano

Italiano Português

Português Español

Español 简体中文

简体中文

More Related Blogs